As promised in the last article on Nara, I'm going to pay tribute to one of my favorite places in the Kansai region -- the beautiful old town of Nara-machi. If you're going to visit Nara's World Heritage Sites, and if you can afford an entire day's time in Nara, then I highly recommend that you read on.

This is the charming antiquated neighborhood immediately south of the famous sights at Nara Park, only fifteen minutes away on foot, yet still missed by most Western tourists coming to Nara. A centuries-old former merchant district, the town has retained its share of ancient temple and old shops from its feudal past, now haphazardly dotting its narrow, mostly residential streets.

As you wander into Nara-machi from the north side (neighboring Nara Park), you leave behind the commercialism of the tourist draws and fall back into feudal Japan. You have no need for a guide, or an itinerary, or even a map -- you are now in the midst of an open-air museum of traditional life in the yester-years. You may touch, smell and even eat some of the exhibits, so long as you are careful not to enter someone's home. In fact so many of the residences are so well-preserved that they would be legitimate museum pieces in most countries, and you wouldn't know aside from the old blankets being sun-dried on the window sills.

This is not a place to rush through with a guided group, or you'd miss the exceptional beauty in the details. Originally established back in the Kamakura period, the lay-out of the modern town is still a haphazard grid of 13th-Century narrow streets and backlanes that appear out of nowhere and terminates into dead ends without warning. Yes you'll more than likely to get lost. But in a place like this, even getting lost is romantic.

Though Nara-machi is not unknown to domestic tourists, it is one of the few examples in Kansai where an entire town of traditional 200-plus-year-old houses has been successfully preserved as a residential area (just compare it to the bustling shop-lined streets of Higashiyama in Kyoto). You'll run into some neighbourhood noodle houses, the odd camera repair shop, or a Ryokan (traditional inn) like this one, but even commercial establishments are housed in their authentic Machiya-style structures.

The Machiya, or "Town-house", is the quintessential Japanese residence of townsfolk before the introduction of western construction techniques in the modern age. Upon your first sight the most striking image would probably be the stark contrast between the dark wooden lattices and the white plaster walls. Almost every front door is a side-scrolling panel of intricate wooden lattice, and almost every roof is an orderly interlocking of traditional earthen tiles.

If you ignore the overhead powerlines and the ubiquitous Toyotas parked on the street side, the entire town retains the same image from a century ago, sometime between the opening to foreign trade in the Meiji era and the wide adoption of western architecture in the Taisho. Here this little cafe "Amachaya" occupies an unknown street corner, supplying the neighbourhood with the exotic taste of charcoal-roasted coffee from the western civilization. Japanese improvization of custard puddings ("Purin" in Japanese) is served alongside fresh baked bread flavored with sweet Azuki beans.

After a few minutes of wandering about the neighbourhood, you'll start to notice one fundamental feature of the Machiya house -- the wooden structure is suspended atop a few independent pieces of foundation stones. Compared to the Western house's stone (or nowadays concrete) building foundation which covers the entire floor area, the Machiya's construction is relatively simple. After a few pieces of foundation stones are places at the corners, wooden beams are placed horizontally on the stones to act as the house's bottom frame. Beams, flooring and room dividers subsequently go on top. The end result is the typical two-storey structure with a tatami-mat floor suspending in mid air, which had been critical for the purpose of improving air-flow and preventing wood decay in Japan's humid summertime.

With or without background knowledge in its construction, one can appreciate the Machiya's aesthetics and the painstaking details that the owner puts into its maintenance and enhancement. This old Chinese medicine shop still hangs its traditional lantern-shaped store signs, though no longer illuminated with an oil lamp.

And if you happen to come from an East Asian background and can read the Kanji, name plates can be very interesting as it will often tells you the family's name, how many people lives in the house etc. This name plate belongs to Mr. Nanji who heads the Nara-machi Archives House.

A fiery red "Shu" character standing out amid a facade dominated by black wooden frames and lattices. Shu, or crimson red, refers to red paste used for the East Asian ink seals (Inkan), so if you're in the market for a traditional personal seal, this is the place to get yours carved.

Just like Austrian Heurigers (wine tavern) hanging pine twigs outside to announce their presence to the townsfolk, the Japanese Sake-brewers do it with these huge cedar balls (sugidama). Even if the sake bottles are too heavy to bring home, you can still enjoy the wine tasting opportunities offered by these sake breweries that you'll encounter all over the country, usually located in older neighbourhoods such as this.

I like taking pictures of sewer covers in Japan. Each city, town or village of major tourist interest seems to have its own special design, as demonstrated by Nara's favorite mascot on this sewer cover. You simply cannot escape from running into the Shinroku, or divine deer, in its various artistic forms wherever you go in Nara.

Wedged between neighbourhood houses in Nara-machi, the Koshin-do is a famous little temple -- it is neither Buddhist nor Shinto, but dedicated to the worship of a monkey deity (Koshin) believed to have halted the spread of a plague 1300 years ago. That's Koshin-san right in the middle, sitting and holding a stone basin on top of its head. Also note the terracotta figures of the three monkeys at the top of the temple.

And you'll see more of these little monkeys at the back of the temple. Note the positioning of the hands of the monkeys -- these are the same "See no evil; Hear no evil; Speak no evil" monkeys made famous by the Tokugawa Mausoleum at Nikko. The wooden plaques in the background are installed here to acknowledge the local businesses providing financial contribution to the construction of the temple. These range from the Koseikan Inn to a traditional medicine company to a soy sauce maker.

Though this residential neighbourhood seems to have a very high concentration of temples of various kinds, the temples generally blend in very well with the dark wooden houses. When you pass by a structure like this without a formal sign, you don't really know whether this is a temple or a restaurant or perhaps simply someone's house.

This one is easier to tell, since the Torii gate always signifies the entrance of a Shinto shrine. This is the entrance to the Goryo Jinja, a small shrine sitting next to the World Heritage Genkoji temple.

Another tell-tale sign of Shinto shrines is the appearance of the thick rope with thunderbolt-shaped paper strips. This shrine is dedicated to a past Emperor and is designated as an Important Cultural Treasure.

I think this is part of the Genkoji temple complex, which is part of Nara's UNESCO World Heritage Site. A group of domestic tourists happened to be passing by, testifying the popularity of this little town which is still relatively unknown to Westerners.

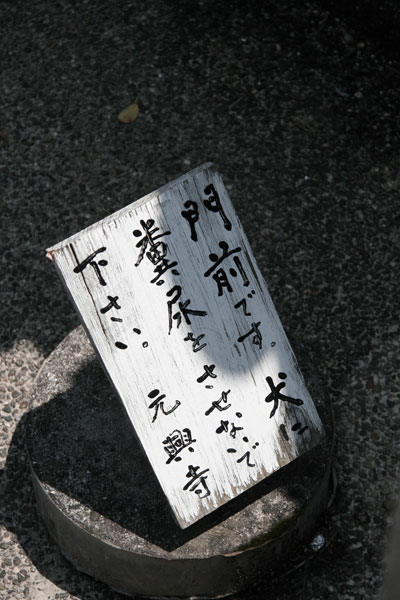

"This is the front entrance. Please do not let your dog defecate or uninate here. Genkoji Temple."

I still haven't figured out whether these are really tombstones -- sure looks like it, but Hello Kitty tombstones? For someone's deceased cats? That is just freaky ... then again, Nara-machi is just full of surprises.

Food Review: TOFU-AN KONDOU (Nara)

Address: Nara-shi Nishi-shinyamachi 44

Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-14:30, 17:30-20:00 (According to Official Site, 2008)

Website/Map: http://www.kondou-touhu.co.jp/

Directions: This is tricky. Starting from the Kintetsu Nara train station, walk straight south for about 10 minutes. **Stop and ask** people where the "Koshin-do" (monkey shrine) is. Tofu-an Kondou is directly south of Koshin-do on the same street.

To tell the truth, we happened to stumble upon the beauty of Nara-machi partially because we decided to check out this little restaurant reputed to be one of the best specializing in Tofu.

Tofu, you ask? Many foreign tourists may not realize that the lowly meat-substitute sold at the vegetarian section of American/European supermarkets is esteemed in Japan as an upscale, traditional fare often served as part of an extravagant meal. Kyoto, just a short train ride to the north, still boasts a large number of restaurants specializing in nothing but Tofu and charges quite a premium for it. At the 360-year-old Okutan Tofu (http://www.frommers.com/destinations/kyoto/D38848.html) the cheapest and simplest 6-course lunch would set you back 3150 yen (CAD$32), which is quite a reasonable price. But you want a larger multi-course meal at a cheaper price? That's where Tofu-an Kondou comes in.

Just like almost every upscale restaurant in Japan, Tofu-an Kondou serves lunches at a significant discount from the dinner pricing. There are only two lunch courses to choose from -- a 13-course "Tofu Kannou" meal for 2000 yen, and a 3200 yen meal with even more courses and an emphasis on Yuba (tofu skin). I don't know about you but a 13-course lunch is quite enough for us.

OK let's count. The first course started with a very rich (the menu says 15% organic soy bean content) soy milk, which was very simply the thickest and creamiest soy milk I've ever tasted. Trust me -- I drink soy milk every morning since I'm slightly lactose-intolerant -- this was good stuff.

The 2nd course was a little dish of boiled whole soy beans (Ni Daizu), marinated in Dashi soy sauce. Nice, but nothing too impressive.

The 3rd course -- the Oboro Tofu -- was a dish where all Tofu makers attempt to stake theirs claims as a top restaurant. I had only heard of this dish before, so this was my first time tasting it. This is supposed to be the softest and creamiest tofu, half-curdled and made on the spot in limited quantity. The restaurant recommended starting the dish without any seasoning at first, then adding a little algae salt, then finally finishing with the addition of Dashi soy sauce.

And it was really the best tofu I've ever had -- rich, soft and creamy, and in my opinion no seasoning was necessary. I did try the algae salt and Dashi soy sauce, which certainly did not overpower the intensely condensed soybean flavor, but didn't add anything special to an already special dish.

Next up would be the most substantial course in the meal -- a pot of silken tofu in broth (Yudofu) in a wax paper container. Shown in the photo was the portion for two persons.

Incredibly smooth texture, and very generous portions too. The taste was a little bland, and the restaurant suggested serving with algae salt, soy sauce, or Yuzu-kosho (a mixture of finely chopped Japanese citron and green pepper). After a few tries I found my favorite combination -- a generous dash of soy sauce with just a touch of Yuzu-kosho.

I apologize for forgetting to photograph the 5th and 6th courses, especially since the 5th course was my favorite in the entire meal.

The 5th course was a sashimi of Yuba, sometimes translated to "tofu skin" but is really the thin coating forming on the surface during the process of making soy milk. Incredibly soft and intensely flavored, I actually enjoyed this even more than the already superb Oboro Tofu. In case you're wondering -- yes it was served with Wasabi and Sashimi soy sauce just like fish sashimi.

The 6th course was a Namafu Dengaku, which was two skewers of wheat gluten grilled with a thick, sweet miso. It was chewy as expected, and the richness of the Dengaku miso preluded a bold departure from the relatively delicate taste in the previous courses.

The 7th course, at the bottom right corner of the photo, was a warm salad -- a Shira-ae of asparagus. What's Shira-ae? Similar to Goma-ae, but replacing sesame dressing with a thick tofu dressing.

At the top of the photo was the 8th course -- a deep fried dish of tofu, oyster mushrooms, lotus root and green pepper.

The next four courses consist of a clear broth with Yuba, a ball of Tofu-vegetables mixture in a Dashi broth, and a bowl of red multi-grain rice, and pickled Hinona turnips.

And finally the 13th course, an excellent Yuzu (Japanese citrus) flavored jelly infused with tiny slivers of tofu, and topped with a sweet bean paste. Perfect balance of sweetness and acidity, and of course the incredible delicateness of the tofu slivers suspended in the transparent gelatin. I can only tell you that it really tasted as good as it looked.

At the end we walked out with very full stomachs, perfect for a long afternoon stroll in the Nara Park. I don't have a star-system in my restaurant reviews, but if I did I would give Tofu-an Kondou the highest rating based on its Quality-vs-Price ratio. Only 2000 yen (CAD$20) for a 13-course traditional tofu meal in a century-old atmospheric restaurant in central Nara. What more can a casual tourist ask for?

Bill for Two Persons

| Tofu Kannou Course | 2000 yen |

| Tofu Kannou Course | 2000 yen |

| TOTAL | 4000 yen (CAD$40) |

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

Transportation

Nara is served by two railway companies -- the quasi-national West Japan Rail (JR), and the private Kintetsu railway. Being in the close of Osaka and Kyoto, many domestic and Western tourists take a sidetrip to Nara while touring the Kansai region. From Kyoto or Osaka it should take roughly an hour and cost a few hundred yens, if you travel by cheap non-Express trains.

Once you arrive at either train stations (JR Nara or Kintetsu Nara), you can get to Nara-machi by local bus number 51, 50, 92, 34, or 35. Get off at the Fukuchi-in Machi bus stop, and you'll be at the eastern edge of Nara-machi. Alternatively, if you're arriving at Kintetsu Nara station, you can reach Nara-machi by walking directly south for 10 minutes.Bus fares are currently 180 yen (CAD$1.8) per trip within central Nara. Or ask for the day pass (say "Ichi-nichi Joshaken" to the driver) for 540 yen if you think you'll take three or more trips.

If you're on the way to somewhere and need a locker to store your luggage, there are lockers of several different sizes at both Kintetsu Nara and JR Nara train stations. The 500-yen (CAD$5) size was enough to stash one large and one small backpacks for us, but there are 600-yen ones which should be enough for 28-inch suitcases.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét