Halfway between Beijing and Pingyao on our route was the city of Datong, home to one of medieval China's greatest monuments, the 1,500-year-old Yungang Grottoes. While the city proper may be described as a highly polluted and uninteresting industrial metropolis, its surrounding region packs enough world-class sights to fill one to two day's itinerary.

The logistic problem though is that the three major sights are somewhat far away from the city, all in different directions. Hiring a taxi (RMB 260-420 as of summer 2011, depending on how many sights) is well worth the time saved to fit everything within one day, especially if you can speak a few phrases of Chinese to tap into the driver's best restaurant recommendations!

So we pre-booked our taxi through email with a reputable company. The team of Pei Ge, Pei Shifu and Yu Shifu (speaks Chinese only; Email: bt6209@yeah.net, Cell: 13503528230, QQ: 825754066) has excellent feedback from the online community of Chinese backpackers (see Q&A in Chinese), and charges reasonable, standard rates for day- and multiday-trips. As of summer 2011 a 10-hour day-trip from Datong to Yungang Grottoes, Hanging Temple, Yingxian Muta, and back to Datong cost about RMB 420. Seeing Yungang Grottoes and Hanging Temple, the region's two most popular sights, cost about RMB 350. Hanging Temple and Yingxian Muta, which are somewhat closer together, cost about 260. Our trip, which includes all three sights PLUS driving us through a treacherous mountain road to Wutaishan for the night, cost RMB 700. In these times of rising gasoline costs (RMB 8 / litre) this is a reasonable deal.

1. THE 1500-YEAR-OLD YUNGANG GROTTOES

We started our morning with the Yungang Grottoes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a spectacular fusion of artistic styles between the Middle East, India and China back in the 5th Century. This isn't just a few statues in a cave, but a kilometre-long series of grottoes carved out of a cliff now containing 50,000 statues, some as tall as 5-storeys.

Official pamphlets won't allude to this, but the ancient artists behind these splendid grottoes were not precisely Chinese. The Xianbei people who carved out the grottoes were often described as "yellow haired" and "pale skinned" in medieval Chinese records, raising speculations that the largely Mongolic tribe contained at least some Caucasian ethnicity. It is no surprise that many of these early Buddhist sculptures hardly looked Chinese.

As many medieval Buddhist monks hailed from modern-day Afghanistan, some of the statues were given deep, Caucasian-like complexions that appear more Middle-Eastern than Chinese. The integration of Indian and even Hellenistic influences resulted in this rare relic at a time of rapid ethnic amalgamation in Northern China, about the same time as the fall of Rome in the Western world.

From the height of its glory as the dynasty's premier religious centre, Yungang Grottoes' significance diminished gradually over the next millennium towards its final abandonment and utter disrepair. Considering all the anti-religious movements, archaeological theft, vandalism and annual sandstorms endured for over a thousand years, the current state of preservation is rather fortunate. This could have easily gone the way of Bamiyan during the Cultural Revolution.

Some of the interior colours are so vivacious, even after 1,500 years of erosion by dust storms, that it's quite easy to imagine yourself inside one of India or Southeast Asia's rock-hewn temples, 5,000 km away to the south. For modern visitors it's difficult to visualize an ancient cultural cross-road to India right here in Northern China, in the middle of the traditional birthplace of Chinese civilization.

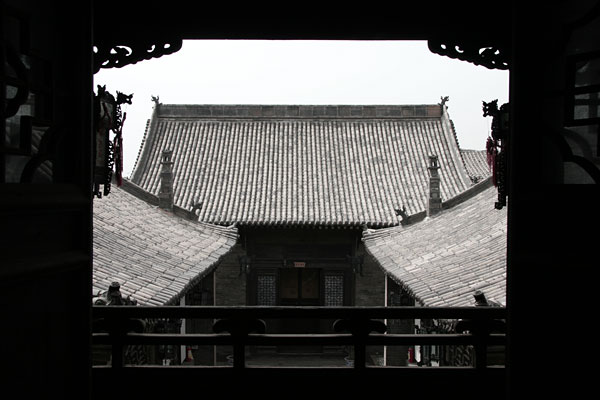

As sun-baked and erosion-prone as the semi-exposed caves may now seem, this was once the crown-sponsored temple of the Northern Wei Dynasty when Datong was the capital. Statues inside were originally protected under a series of roof extensions built into the cliff-face, though most of the wooden structures and even part of the earthen roofs have collapsed over the centuries. Now all that remains of the roof extension is a 4-level Qing Dynasty structure protecting grottoes No.5 and 6.

The provincial government currently has plans to extend the protective structure over a few more of the grottoes as a barrier against the annual springtime sandstorms bearing down from the Gobi Desert. Hopefully the governing body will get it right and avoid spoiling the authenticity of the scenery, though I'm not entirely optimistic considering how the government managed to screw up Wutaishan. And with the cost of entrance tickets rising almost every year, visit sooner rather than later if you can.

Yungang Grottoes are located about 30 minute's taxi ride northwest of Datong's city centre, though the stretch within city boundary seemed to be prone to traffic jams. Our taxi driver Yu Shifu picked us up at 08:00 and arrived at Yungang around 08:45, right around its official opening time. Though the actual grottoes took less than an hour for us, the rambling, brand new complex of souvenir shops and restaurants added at least another 30 minutes to navigate. Plan for a 2 hour visit to be on the safe side.

2. THE HANGING TEMPLE OF HENGSHAN

Advertised by Time Magazine as one of the world's Top 10 Most Precarious Buildings, the Hanging Temple (Xuan Kong Si) is another one of Datong's 1,500-year-old treasures and one of the most photographed sights of Northern China. This is an absolutely breathtaking spectacle that every visitor to Datong should see, though perhaps not everyone could summon the courage to enter.

Constructed at roughly the same time as the Yungang Grottoes, the Hanging Temple is a brilliant piece of medieval engineering from the 5th Century. To the awed observer underneath, the temple seems to be supported dangerously by a few lanky wooden poles jabbed vertically into the already near-vertical cliff side. If you still can't imagine, think of an apple pie fastened to the side of your fridge by a few toothpicks underneath.

Except the toothpick-thin support was a rather late addition only 600 years ago, and could be removed entirely without throwing the temple and its army of tourists down the treacherous cliff. Ancient engineers ingeniously reinforced the structure through a system of crossbeams inserted right into the rock face, safely securing it against earthquakes and cliff erosion for the past millennium and a half. Even Li Bai, China's most famous poet, gave his approval over a thousand years ago with an oversized work of calligraphy that is now engraved at the bottom of the cliff.

For entrance fees as steep as the drop under foot (RMB 130 for a crowded 20-minute walk!), visitors get the chance to confront their own worst feelings of vertigo inside the small wooden temple with the vertical rock face on one side and a heart-stopping plunge to the valley floor on the other. I've been to another so-called Top 10 Most Precarious Building at Meteora, Greece, and this one was definitely scarier.

It's actually not as intimidating as it sounds -- you just have to turn off your intellect and stop questioning China's safety standards on the wooden planks and railings, and at the same time hope that the lady at the entrance doesn't let too many zealous tourists enter the structure at once. There is no turning back once you enter, as the route is marked out in a one-way loop of the multi-level temple. Backtracking would be even more dangerous as you would need to squeeze past the oncoming queue along the precariously low railings.

The Hanging Temple and the surrounding Hengshan area are currently included on China's tentative list for incorporation into Mount Taishan's UNESCO World Heritage Site, and you can expect the number of visitors to skyrocket ... and the entrance fee to further increase ... if it becomes accepted. Shanxi Province now has three UNESCO sites and five on the tentative list -- this just shows the incredible richness of cultural heritage at this often overlooked corner of Northern China.

A tour of the Hanging Temple took us roughly an hour, with enough time to wander around the cliff bottom (but not too close!) to find the best photo spots. It did take a long taxi ride to get to the Hengshan area though – taking about 2 hours from Yungang Grottoes (or 1.5 hours from Datong's city centre) in mid-day traffic. Our taxi driver recommended a good and inexpensive lunch spot near the temple, which I'll try to review in the next article.

3. THE LEANING TOWER OF ... CHINA?

Another hour-long taxi ride from the Hanging Temple took us to the least well-known of Datong's incredible works of medieval engineering -- the Yingxian Muta (literally Wooden Pagoda of Ying County). Officially named Pagoda of Fogong Temple, this place is so amazingly underrated that most Chinese citizens outside of Shanxi Province have never heard of it. Even less people know that it is not only the world's tallest fully-wooden structure at 67m (220 feet), but also one of the world's oldest wooden structures at nearly 1,000 years old.

Like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, it is also tilting perilously to the point that visitors are now restricted to only the first two levels. Compared to the world-famous Italian landmark, the Wooden Pagoda is actually 10m taller, more than 100 years older and, unfortunately, currently leans further at a rumoured 6.5 degrees. It should have already achieved international fame, except for its remote location on the Loess Plateau, 70km south of the closest major city of Datong.

Travelers venturing this far are rewarded with a close view of the astonishing craftsmanship of the oft-vilified Liao Dynasty, whose architects designed the massive structure entirely out of wood joinery without any metal nails or fasteners. Unfortunately the pagoda has been showing symptoms of major structural distress for decades, and despite heated discussions for the past two decades, experts still cannot agree on a single plan to save this 1,000-year-old relic from imminent collapse.

At the time of writing there seems to be a serious bid by the provincial government to fast-track the Wooden Pagoda as a UNESCO World Heritage Site candidate. Visitors can only hope that this will result in quicker action to start saving the pagoda for future generations.

It was 16:00 in the afternoon by the time we left Yingxian, en route to our stop for the night at yet another UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Buddhist mountain community of Wutaishan.